Recently I did a thing which I have planned for a long time, but never quite found the confluence of time, money and motivation to complete: I got a tattoo.

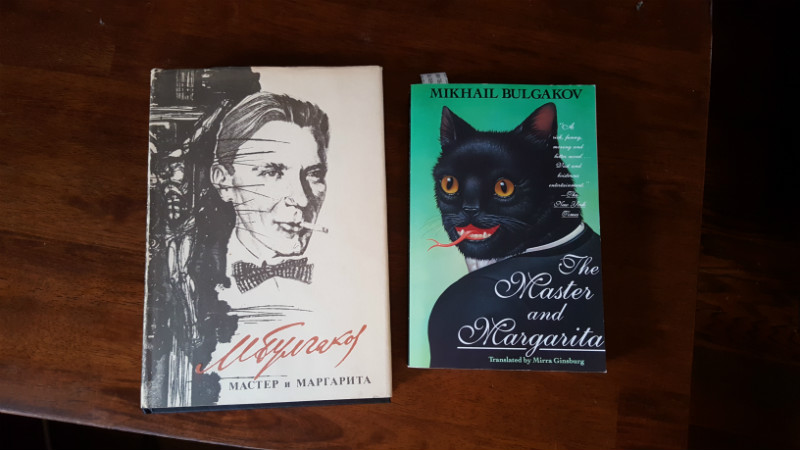

It’s a quote in a cursive Cyrillic typeface, reading “Рукописи не горят” (“Manuscripts don’t burn”) from the book The Master and Margarita, by Mikhail Bulgakov. Nick, one of the artists at Mos Eisleys Tattoo Studio, did the inking.

“But John,” I can hear you say, “Why?”

Why, indeed. Here are my thoughts on the subject, framed as a conversation with an imaginary me, a technique which I steal, with attribution, from one of my favorite writers, John Scalzi:

Why get a tattoo?

Short answer: ‘cause.

Full answer: I’ve been meaning to get a tattoo for a long time, probably a decade. Of the many ideas and impulses, few felt right for more than a few months or a year, which is not a great basis for getting inked.

Earlier this summer my girlfriend Zyra got her first tattoo, a traditional Filipino pattern done in the traditional style by Lane Wilcken, one of the very few practicing traditional artists in the world. Lane and Zyra invited me to participate in the tattoo ceremony, and I help stretch Z’s skin while Lane inked her leg. This experience tipped me over from “might” to “will,” and now I have a tattoo.

Why in Russian?

I was a Russian Studies major in college, and spent a semester studying in Saint Petersburg and Moscow. In that time and since I have read many book by many Russian authors. For a time in the early 1990s, I was nearly fluent. I have in my house dozens of books of Russian literature, poetry, plays, philosophy and artwork. Russia, or at least the literary parts of Russia, have been quite influential in my life for decades.

I don’t remember if I first read The Master and Margarita when I was in college, or after I graduated. I do know that I was not at all ready to be in the real world when I did graduate, so I immediately went to work at a local bookstore. There I had my fill of Russian literature. So it was sometime in the early to mid- 1990s.

In early 1994 my former Russian Studies professor, Christine Rydel, hunted me down and coerced convinced me to rejoin the RST program for a semester in Russia. During that trip I learned a great deal of Russian, drank an ungodly amount of vodka, and visited the studio of artist Andrei Kharshak (Андрей Александрович Харшак, see also), who had created a series of illustrations for an edition of The Master and Margarita published in Russia in 1994. I came home with two prints – one of Golgotha and one a sort of collage which includes a scattering of pages around a stove, echoing the scene where Satan, in the guise of Woland, tells the despondent Master “Manuscripts don’t burn.”

Over the intervening years Russian literature as an influence in my life has waxed and waned. With my (relatively) recent and (apparently) ongoing interest in literature in translation, Russian Lit is now ascendant. And with Russia influencing American politics, and thus the American zeitgeist, getting the tattoo in Russian just felt right.

Why that particular quote?

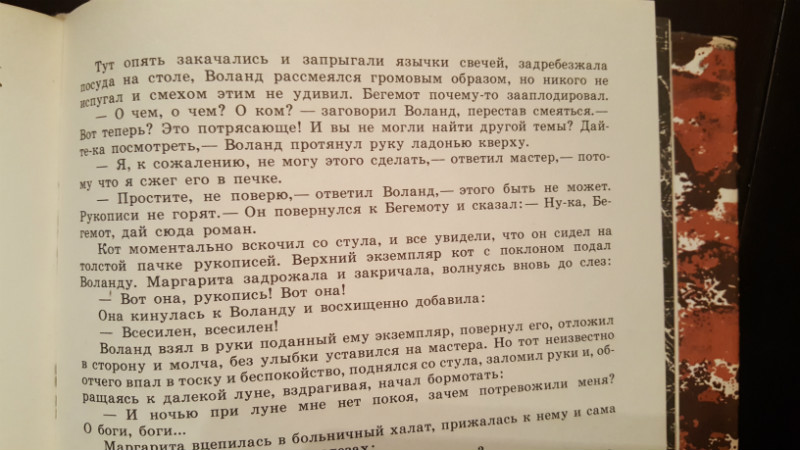

The quote, in context, appears at the beginning of the tenth line in the above photograph.

“Manuscripts don’t burn,” in the context of the book, carries the connotation that a work of art, once created, lasts forever. The Master’s book is censored by Soviet bureaucrats and he burns the manuscript. Later on, Woland and his entourage produce via sleight of hand the unharmed manuscript, stating “Manuscripts don’t burn.” The physical artifact may be destroyed, the artist may disown and disavow its existence, but for good or bad, a thing created cannot ever be un-created.

I find in this sentiment echoes of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, in these lines:

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

Once an act is performed, the universe is now one in which the act was performed. Or as Buddhists would put it, only our actions are permanent.

In a larger sense, Bulgakov wrote his book at a time when official government censorship (and censureship) prevented the publication of many works of art and literature. The Master and Margarita, written between 1928 and 1940, wasn’t published in full until 1967, and even then first in France. Yet Bulgakov persisted, and now The Master and Margarita is counted among the most important works of Russian literature.

Aren’t you kind of overthinking this whole tattoo thing?

Well maybe, but it’s a tattoo. It’s kind of permanent.

Permanent?

In the context of my corporeal existence, or at least that of my left arm.

Are you going to get another tattoo?

I think so. This was a great experience. Assuming time, money, health, etc., I will probably get at least one more before the end of the year. I have a few more ideas, and I have thought about them long enough that having more words on my skin will be neither impulsive nor disruptive. At least one will be on more visible skin.

Thank you for sharing.

Thank you for listening!